GALLE HERITAGE

PROJECT —

A PLAN TO GIVE A FUTURE TO THE PAST SUGGESTIONS

FOR A PRELIMINARY PILOT PROJECT: BLACK FORT

Lodewijk J. Wagenaar

INTRODUCTION: Although the Galle peninsula and surroundings were

inhabited before the colonial era, and although Punto de Galle was given

its first European colonial shape by the Portuguese, this memo will deal

mainly with the Dutch Period, and modestly with the British Period and

the period after the colonial occupation, since most of the fortress, the

buildings and the city grid dates from post-Portuguese years.

To understand the Fort of Galle as an organism one must understand the

small city in its organic and functional aspects. In the Dutch Period (and

similarly in the Portuguese Period) one may emphasise four main aspects:

-

maritime: the port, the related workshops and the warehouses;

-

administrative: the administration of the Fort itself and of the surrounding

Galle district, the latter through local headmen;

-

economic: the relationship with the immediate hinterland producing rice,

coconuts, areca-nuts, cinnamon, timber, etc, as well as the relationship

with the sea, ie fishery;

-

military: defence against European competitors, and safeguarding against

the Singalese, especially the Kingdom of Kandy.

In the British Period most of the maritime activities were transferred

to Colombo, after the construction of the new harbour with its breakwaters

and quays (before that time only the roadstead was in use). The emphasis

on the cinnamon trade in the Dutch Period shifted to other agricultural

crops serving new market demands (coconut, oil, rubber, and tea). The Dutch

Burghers adapted well to the new British occupants and rose on the social

scale; 19th and early 20th century society and daily life were strongly

influenced by the Burghers. Since the late 18th century, a new town grew

up outside Galle Fort. From 1800 onwards, more and more Singalese and Moslem

people entered Galle Fort.

To avoid misunderstanding: Burghers were originally Dutch East India

Company servants who obtained permission to leave the service to settle

as private small scale entrepreneurs. Their children, many of them born

of mixed relationships, automatically received Burgher status, although

many of these Eurasians entered the service of the Company (VOC). Only

later, in the British Period, all descendants of Europeans and Eurasians

were categorized as ‘Burghers’, among them the so-called Dutch Burghers.

Their way of life, of which the poffertjespan, the Broedercake and the

verandah cum stoep are evocative, derived from the early Dutch Period.

The verandah is an 18th century development, but the general layout of

the Dutch Period house has early origins. It is remarkable to read in 18th

century sources that many houses still had no tiled roofs, which were again

and again ordered in city regulations to prevent fires. In marked contrast

to Batavia, in Galle (and also in Colombo and Jaffna) the tiles in use

were of Portuguese style, and not the Dutch ‘gulf’ tiles. Already in the

Portuguese era the tiles were locally made.

Life in Galle was of mixed European–Asian character. In Holland one

will look in vain for colonial structures such as these, which are similar

to those on the Iberian Peninsula, and quite well adapted to the Asian

situation. In Amsterdam land was scarce and every merchant wanted his warehouse

close to the canals, so warehouses there were deep and high; in contrast

the warehouses in Galle are lengthy and low. The fortifications too were

different in the East: in Europe they had to cope with more sophisticated

gunfire and techniques of warfare; in Asia the fortresses could make do

with more basic structures. Only in the 18th century this changed, especially

in Galle, Colombo and Jaffna. Documents in the VOC archives in Colombo

and The Hague, as well as drawings and plans, make this perfectly clear.

BLACK FORT: SUGGESTIONS FOR A PILOT PROJECT

In the long run it may be possible to have a series of places, buildings

and houses showing different aspects of Period Daily Life. In the future

one may acquire a Dutch period house to turn into a show house with period

rooms, kitchen etc. Other buildings and places may be used to show aspects

of daily life in the past, from various periods in the long history of

Galle. However, since it is wise to start simply, it is advisable to begin

with only one project, which has potential to combine several ambitions:

-

preservation, conservation and reconstruction;

-

stimulation of public and institutional awareness of the cultural heritage;

-

training of local craftsmen, contractors, architects, scholars, civil servants

and laymen, with transfer of experience and know-how from the Sri Lankan

capital as well as from abroad;

-

generation of income by a new management of cultural heritage, linked with

modern policies to foster cultural tourism, private/public enterprise,

presentations of living history, guiding by ‘cultural narrators’, information

centres and modern museums.

Black Fort is a suitable spot to start a project to materialise these ambitions.

It is easy to link this place with the old Dutch Warehouse (to become a

Maritime History Museum) and the Bay Area at the jetty-side. This could

become a Nautical Quarter, as advocated long ago by Ashley de Vos, the

Sri Lankan godfather of a new understanding of Sri Lankan architecture

as being of ‘dual parentage’.

The Black Fort is the earliest fortress in Galle, with roots in the

late Portuguese Period, showing strong Dutch influences but also traces

of use in the British Period including the Second World War as well as

of use in the post-colonial era. Thus the Fort is ideal to bring to life

several aspects and periods. Cannons (replicas), other related equipment,

tools and cannonballs may be placed, smaller structures may be erected

which sheltered the gunpowder barrels, etc and guardhouses might show soldiers

from different periods doing their job (that is: doing nothing but waiting).

Volunteers or paid actors might do exercises at scheduled times to bring

the history to life; however a permanent and noisy show like that in Williamsburg,

USA should be avoided.

Reconstructed or conserved buildings within the Black Fort might be

turned into museum-like places, offices, kitchens etc. At the lower level

an extremely attractive restaurant could be located, with access to the

jetty area. There the tiny shipyard could be brought back into life, to

build dhows for harbour trips and fishermen. History can pay!

This Black Fort Project, part of the greater Galle Heritage Project,

can easily be linked with the other Galle-linked project, the Galle Harbour

Project, aimed at the identification and research of shipwrecks in the

Galle Harbour. The laboratory at the jetty can be a temporary information

centre for the two projects. Video films and other vivid information will

make this information centre a lively and interesting one, and during underwater

excavation the work in progress can be shown on a monitor. Objects undergoing

conservation may be shown, and after treatment they will be on display

in the Maritime Museum of Galle. A very interesting result of this Galle

Harbour Project is that ship parts have been identified from early times.

Ancient stone anchors of Arabian pattern and the Sung dynasty Chinese bowl

found in the harbour prove the continuity of maritime history in Galle

Bay.

As the Batavia Wharf in Lelystad, Netherlands, has already proven, the

interest of the general public in research and exhibits of this type is

tremendous. Without doubt, history can offer interesting financial returns.

To start with it is suggested to conduct research in the VOC archives

in Colombo. Maritime history, economic history, and the history of building

and maintenance activities are fully documented as far as the 18th century

is concerned. For earlier periods, VOC documents in the General State Archives,

The Hague, Netherlands, have to be studied. The National Archives in Colombo

however give good possibilities for a start. The documents there from the

VOC settlement in Galle give ample information, especially the monthly

reports and the yearly compendia of the various VOC departments (the smithy,

ship repairing and building departments).

Most movements of ships have been recorded, not only of the great East

Indiamen, but also of the smaller ships: not only Sri Lanka based VOC ships,

but also ships arriving from other ports of the VOC trade empire. Even

movements of ships owned by Moslems and Burghers have been recorded and

mention has been made of visits by other European ships.

The building history of the Dutch Forts is well recorded. Weekly and

monthly reports on the maintenance, complete with lists of used materials

and labour give wonderful information. Special reports give information

on the state of the forts, related with the wars in Asia between France

and Britain (eg the Seven Years War, 1757–1763) or with the aftermath of

the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War (1780–1784), in which the French were also involved.

In 1795, another war broke out between the Dutch and the British, who then

took over Galle in February 1796. A report from 1795 states that the forts

in Ceylon were so badly maintained that even saluting with the cannons

proved ruinous to the structures.

Students from Holland may make an overall review of these reports, so

that the Galle Project Team can translate this into the conservation, preservation

and reconstruction programmes.

To get the programme started it might be considered appropriate to appoint

four officers:

-

liaison officer within the framework of the Galle Heritage Foundation,

based in Galle, as an officer who connects the several institutions and

responsibilities shared by the GHF-partners, and who within this framework

and appropriate parameters can act with delegated authority. This person

should have a facilitating role, mediating between the relevant organisations

on the one hand, and between the GHF and the public;

-

a cultural project manager, next to the overall project manager, who coordinates

the several scholars and other specialists (museologists, archaeologists,

restoration and conservation architects, guide-trainers, etc) and their

sub-projects;

-

an architect with expertise in translating cultural and daily life history;

-

a ‘living history’ museologist who sets up plans for a visitor centre,

museum-like exhibitions, outside exhibits, performances, light-and-sound-shows,

parades, etc.

These positions are not necessarily full time. There will probably be possibilities

to combine some of these functions in one person. The tasks and responsibilities

should be clearly defined, as should the relations between the several

managers.

The Black Fort Project might function as a pilot study, to be used for

other projects of the chain. By training craftsmen, students, staff, contractors,

etc, experience will be built up, which may be used for other projects,

even for projects in other parts of Sri Lanka. As far as cooperation with

universities is concerned, it might be advisable to create pairs of Dutch

and Sri Lankan students who work together on the same (sub)project and

to link them with a span of Sri Lankan and Dutch specialists as tutors,

thus ‘sandwiching’ them to guarantee the most efficient way of getting

the desired results. To start with, a workshop could take place, where

the identified projects can be worked out, with time-frame and management

planning. Within five years the Fort of Galle could operate as a world-famous

example of how to enjoy the past in the present, with attractive effects

on job creation and on the welfare of the inhabitants of Galle and the

region. The year 2002, four hundred years after the visit of Joris van

Spilbergen and the foundation of the VOC, might be an extra incentive for

sponsors and investors.

PARTNERSHIP: A LIST OF PARTNERS TO BE CONSIDERED

An enterprise like the Black Fort Project should be split up in smaller

projects, to make it easier to realise. For the British Period cooperation

with the Imperial War Museum in London and with the St. George Fort Museum

in Madras would be interesting. As far as the Dutch Period is concerned,

the Army Museum in Delft and the Vesting (Fortress) Museum in Naarden should

be considered. The National Archives in Colombo and the General State Archives

(ARA) in The Hague will be partners; universities in Sri Lanka as well

in the Netherlands, Leiden (RUL) and Amsterdam (UvA) might cooperate in

sending experts and trainees; museums like the Amsterdam Historical Museum,

the Maritime Museums (Amsterdam and Rotterdam) and the Rijksmuseum (Amsterdam)

could be involved. The Netherlands Department for Conservation (RDMZ, Zeist),

ICOMOS (Netherlands), the Dutch Department for Education, Culture and Sciences

(OCW) and the Culture Section of the Dutch Embassy in Colombo could be

important counterparts, because they will be interested in giving structure

to training programmes to foster preservation and conservation, the transfer

of experience and know-how, directed to stimulate cultural tourism, which

might generate funds for implementation of the plans (hardware, staff,

training) as well for maintenance of buildings and fortifications. The

Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies (IHS, Rotterdam) will

be an attractive partner to train staff in organising and executing new

tasks, which like those of the scholars and architects will be interdisciplinary,

even ‘cross cultural’.

The Dutch counterparts may be asked to consider co-financing the costs

of Dutch trainees and specialists/consultants, training programmes, etc.

The ‘hardware’ itself, conservation, preservation and reconstruction will

be for the greatest part the responsibility of the Galle Heritage Foundation

and other Sri Lankan institutions (Ministries, Departments, UDA, Southern

Province, Southern Development Authority, Municipality of Galle, etc).

However, financial partnership in the form of private/public investment

might create real possibilities for private investors and sponsorship.

Legal aspects of this are worth separate study.

GALLE FORT: CENTRE FOR CRAFTSMANSHIP,

KNOWLEDGE AND PUBLIC AWARENESS

Ypie Attema

INTRODUCTION

On behalf of the Netherlands Department for Conservation, I propose

that the World Heritage Site at Galle Fort should be developed into a major

restoration centre.

In developing Galle into a major heritage site and a small-scale tourist

destination, restoration activities can play an important role: for instance

in on-the-job

training of local craftsmen and in familiarising the public with old

buildings and crafts. An approach combining restoration activities, special

technical training, and the raising of public awareness, could be a pilot

project with a strong multiplier effect, not only for Galle Fort and its

surroundings, but also for the revitalization of other historic sites in

Sri Lanka.

NOTES ON RESTORATION

If we want to develop Galle Fort as a place of major historic interest,

we have to formulate valid arguments for the character the Fort should

exhibit. Should we stress one single period, or would it be better to show

the history and development of Galle Fort through the ages?

There are many important questions to be answered: for instance, on

what information should a restoration be based and which building materials

should be used? To answer such questions, the objects themselves are the

best guide, in combination of course with written and other sources.

NOTES ON TRAINING

Restoration activities can function very well as technical training

programmes for architects and craftsmen and can educate the public at the

same time. The Netherlands has valuable experience with these training

programmes, which focus on four major objectives: education of craftsmen

in the field of restoration; rehabilitation of objects of cultural and

historical value; integrated urban heritage management (town renewal approach);

strengthening of social-economic infrastructure and housing and infrastructural

strengthening for tourism and recreation.

Within this framework, many worthwhile monuments have been restored

in the Netherlands during the last ten years, including churches, houses,

a station, several water and wind sawmills and a factory which produces

bricks for restoration purposes. In Sri Lanka there is also some experience

with this type of training-on-the-job: in Galle Fort the restoration of

the pulpit in the Dutch Church has been carried out as a training project

of craftsmen.

NOTES ON TECHNICAL ASPECTS

Decisions also have to be taken regarding the building materials to

be used: bricks, tiles, plaster, mortar or concrete? Each has specific

qualities which must be taken into account. Climate must be considered:

different building materials are required in a damp and salty climate than

in dry conditions.

For future restoration in Galle Fort, there are specific questions

on the use of materials: Which common materials should be used? What

special treatment do they need in this climate? Which modern, alternative,

durable and low-maintenance materials can be utilized? and, very importantly:

Do these materials harmonize with the original or desirable character

of Galle Fort?.

THE IMPORTANCE OF SETTING UP A DATABANK

To answer these questions we have to research the original building

materials in relation to the specific climate of Galle. Ideally the outcome

of these investigations should be stored in a databank. Data gathered during

archaeological fieldwork, or the results of technical documentation and

dendro-chronological research, should be stored likewise.

A databank on the research and building activities in Galle Fort could

also provide useful information for restoration projects elsewhere in the

country.

THE IMPORTANCE OF REGULAR MAINTENANCE

Once a building has been conserved or restored, it has to be kept in

good shape. At the first stage of developing plans and budgets for restoration,

one must take into account the costs for short, medium and long-term maintenance.

Prevention is better than cure.

This is the motto of the Monumentenwacht, a successful Dutch organization

which, on the basis of an annual subscription, carries out regular inspection

of buildings and repairs small defects. Larger repairs have to be done

by regular contractors. At present, around 12,000 out of 50,000 monuments

in the Netherlands have joined this valuable organization.

CONCLUSION: GALLE—A CENTRE FOR CRAFTSMANSHIP AND EDUCATION

While developing Galle Fort into a major heritage site and small-scale

tourist centre, it can also become an important centre for craftsmanship

and education. This would make a valuable contribution to the development

and activation of restoration integrated conservation activities throughout

the country.

HERITAGE FIELD SCHOOL

AND PUBLIC ACCESSIBLE EXCAVATION IN GALLE

Robert Parthesius

As shown during this seminar, the city of Galle and its harbour have

an extensive reservoir of heritage sites dating from around the 10th century

(stone anchors) to the present day. Due to its strategic position in the

Indian Ocean, Galle has served for many years as a junction of cultures.

The presence of these cultures is seen by traces left in the city and on

the sea bed. The Dutch left a significant impression in Galle: the fort

as a complete city formed in the 17th and 18th century, five East Indiamen

in or around the harbour and an extensive Dutch archive in the National

Archives in Colombo.

The potential to use these ‘cultural resources’ for training, research

and presentation purposes is obvious. Over the years several projects have

been initiated based on this gold mine of information. During this seminar

you have been introduced to some of these projects, and plans relating

to the cultural heritage sites in Galle.

The Galle Harbour Project has located and surveyed over twenty sites

of archaeological importance since 1992. In 1996 and 1997 some small-scale

excavations have been carried out. In 1992, 1993, and 1997, groups of Sri

Lankan archaeologists have been trained in maritime archaeology and conservation.

The Conservation Laboratory, located on the import jetty, is nearly completed.

In previous years small projects have been carried out, focusing on

the many monuments in the fort; one example is the restoration of the pulpit

in the Dutch Church. The primary goal in this particular project was to

establish restoration know-how in Sri Lanka through on-the-job training.

This expertise can be used in future for preserving other monuments.

The Black Fort proposal echoes this objective and adds another: the

presentation of the past to the general public.

Training is important to develop the skills to research and preserve

Sri Lankan heritage. Equally important is the ability to explain and exhibit

the past to the general public. Public awareness will lead to general support

for this important work, especially if the local economy benefits from

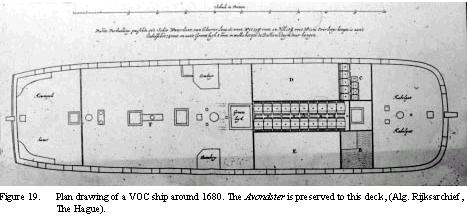

cultural tourism.Figure 19. Plan drawing of a VOC ship around 1680. The

Avondster is preserved to this deck, (Alg. Rijksarchief, The Hague).

FIELD SCHOOL

To achieve these goals for heritage sites in and around Galle, it is

important to work as much as possible in co-operation: locally, nationally

and internationally. In order to profit from each others’ experiences and

skills, and to avoid duplication of infrastructure, it has been suggested

that a field school be established. The general philosophy would be to

have a co-ordinating centre for research, reporting, training and presentation

activities. The field school would be involved in a range of disciplines

including maritime archaeology, heritage management, material conservation,

historical research, etc.

Within the Galle Harbour Project a field school of this kind has evolved.

As you have heard today, an extensive programme of research and training

has been established. The laboratory in Galle will be a permanent centre

for further research and training in the conservation of maritime artefacts.

After this expedition we hope to have a team of diving researchers with

the basic skills for maritime archaeology. To extend the programme with

other areas of research and training, such as heritage management or restoration

techniques important for the other projects, we hope to set up a small

education centre including a library, workshop room and housing facilities

for students and scholars.

PRESENTATION

It is important to develop various forms of presentation. For the Galle

Harbour Project we can think about several. First there should be written

reports and newsletters.

The laboratory on the import jetty near the old gate is an important

step to show the maritime heritage to the general public. Through organised

tours, visitors can see conservation work in progress on objects from the

shipwrecks in the harbour. The cleaning of the stone anchors next to the

Maritime Museum is the first open presentation of finds from the sea bed.

After conservation, the objects and associated information should be

moved to the Maritime Museum. A permanent display supplemented with temporary

exhibitions should do justice to the important maritime history of Galle

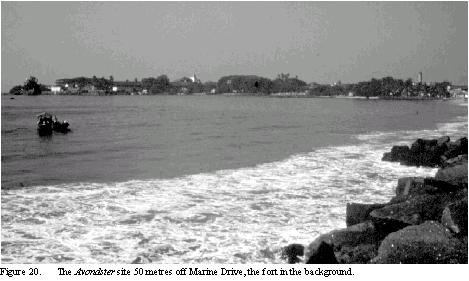

and its role in the ancient trade routes.Figure 20. The Avondster site

50 metres off Marine Drive, the fort in the background.

A very tempting idea is to set up a whole chain of presentations around

the maritime archaeological activities in the harbour. The natural starting

point would be the excavation. Normally this is difficult in the case of

underwater work, but it is not impossible. The wreck of the VOC ship Avondster

provides us with an unusual opportunity to integrate the excavation work

into a public presentation. The ship is in remarkably good condition up

to the main deck. The wreck is in shallow water, only 50 metres off Marine

Drive. A simple jetty would allow the wreck to be accessed from the shore.

Seeing actual work in progress on site has always proved very popular with

visitors. In my vision locale guides can organise tours for cultural tourists

around the various heritage sites.

The Dutch invested heavily for their own profit in the 17th century

and the ships and infrastructure which they financed are now a most valuable

asset for the community of Galle and for Sri Lanka. Cultural profit, scientific

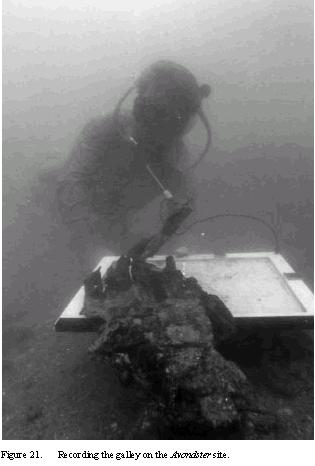

profit, and commercial profit should go hand-in-hand.Figure 21. Recording

the galley on the Avondster site.

GALLE HARBOUR: THE FUTURE

Jeremy Green

INTRODUCTION The Galle Harbour project has made a considerable

achievement in the development of understanding of Indian Ocean port cities.

We have evidence of trade from early times to the modern day. Shipwrecks

abound in the harbour. The project is at an important turning point for

the development of maritime archaeology as a discipline in Sri Lanka. There

are a number of objectives still to be achieved and there are a number

of initiatives that need to be developed over the next three years. Firstly

there is a need to complete the survey work in the east part of the harbour;

the conservation laboratory needs to be finished; further exploration of

other parts of the inner harbour is required; the Avondster site requires

further investigation and the development of a management plan; the known

but as yet undiscovered VOC shipwreck sites need to be located and further

exploration of the outer harbour is required.

THE EASTERN HARBOUR SURVEY The survey of the eastern part of

the harbour was partially completed in October–November 1997, however,

at the end of the season some magnetometer targets were uninvestigated

and some magnetometer survey work is still to be completed. The presence

of large iron wreck sites in the eastern part of the harbour have made

it difficult to identify the VOC shipwrecks thought to have been lost in

this area. Further careful magnetometer survey, together with the use of

high resolution PC Side-scan Sonar may make the location of the sites possible.

For the present, however, the eastern part of the harbour has only been

partially examined.

THE CONSERVATION LABORATORY The Conservation Laboratory should

be completed by the end of 1997, until this facility is complete, it is

not possible to conduct any major archaeological excavation work in Galle.

The facility will be an extremely useful part of any maritime archaeological

programme in Sri Lanka and will help to establish Galle a centre for maritime

archaeological studies.

FURTHER SURVEY OF INNER HARBOUR The area close to the Black Fort

and know to be a lightering point merits further investigation. To date

this site has yielded five stone anchors, raising interesting issues relating

to dating and use. We know that a bronze statue was found in the same area

by local divers and the whole area is covered with large quantities of

artefacts of various periods. The area merits a thorough archaeological

survey, firstly to delineate the extent of the site and then to determine

the depth of burial of the material. This area is likely to be of particular

interest because it was, traditionally, the anchoring site for Galle. Since

Galle, until the construction of the Fisheries Harbour, did not have a

quay, all loading and unloading was by carried out by lighters. It is very

likely that there is material dating from before European presence in the

Indian Ocean.

THE AVONDSTER SITE Certainly the most exciting underwater archaeological

site in Galle, this site has enormous potential. Being within 50 m of the

Marine Drive, excavation of the site can be shore-based. With adequate

funding, the site could be excavated dry within a coffer dam. The site

is exceptionally well preserved and known to contain material of considerable

interest. It could also be the focus of a ‘cultural tourism’ programme,

linking the excavation site with the Maritime Museum and the city of Galle.

As indicated above by Parthesius, a detailed survey of this site is required

together with the development of a management plan for the site.

THE OTHER VOC SHIPWRECKS

We know from the archival research that there are at least three other

unlocated wrecks in the harbour. It may well be that these sites are as

well preserved as the Avondster. Future survey work will help to locate

and identify these sites. The maritime archaeological legislation proceeding

through Parliament at present will ensure the protection of these sites

in the future. There is no doubt that Galle has a unique place in the history

of the VOC, particularly because of the number of shipwrecks.

TRAINING With the development of the maritime archaeological

training programme, it is likely that in the near future there will be

a small maritime archaeological unit in Sri Lanka. Within the next few

years it may be possible to undertake an advanced training programme to

develop and extend the existing skills within Sri Lanka. Furthermore, given

the facilities and expertise available, it could be possible for Sri Lanka

to become a regional training centre for Indian Ocean and Southeast Asian

countries. Such a training centre and programme would be particularly opportune,

given that Thailand no longer operates an Asian maritime archaeological

training programme. The diversity of sites that Galle has to offer, the

extent of cross-disciplinary interests, the international interest and

involvement makes this an attractive and exciting proposal.Figure 22. The

November 1997 GIS plot of the survey work in Galle Harbour.

LIST OF SPEAKERS

S.U. Deraniyagala Director General of Archaeology

Gihan Jayatilaka Advisor Maritime Archaeology for the Department

of Archaeology, Sub-Aqua Club and Maritime Heritage Trust

Jeremy Green Western Australian Maritime Museum, Australian

National Centre of Excellence in Maritime Archaeology

Robert Parthesius University of Amsterdam

Rukshan Amal Jayewardene Archaeologist, Trainee Maritime Archaeology

Jon Carpenter Department of Conservation, Western Australian

Maritime Museum.

Nerina de Silva Conservator, Consultant Galle Harbour Project

Somaseri Devendra Senior advisor Galle Harbour Project

Lodewijk Wagenaar Amsterdam Historical Museum

Ypie Attema Netherlands Department for Conservation

LIST OF ATTENDEES

Ms Drs Ypie Attema Netherlands Department of Conservation

Mr Patrick Baker Western Australian Maritime Museum

Ms Claire Barnes Volunteer, Galle Harbour Project

Mr Jon Carpenter Dept of Conservation, Western Australian Maritime

Museum.

Mr W.M. Chandraratne Central Cultural Fund

Mr Tom Dawson Department of Archaeology

Mr A.M.A. Dayananda Central Cultural Fund

Dr S.U. Deraniyagala Director-General of Archaeology

Lt-Cdr Somasiri Devendra Senior advisor Galle Harbour Project

Dr Malimi Dias Director of Epigraphy and Numismatics, Department of

Archaeology

Ms Indrani Fernando Department of Archaeology

Ms Jinky Gardner Dept of Underwater Archaeology, East Carolina University

Mr Mike Gardner Ms Dena Garratt Western Australian Maritime Museum

Mr George Green Volunteer, Galle Harbour Project, WA Maritime Museum

Prof Jeremy Green Western Australian Maritime Museum

Mr Gihan Jayatilaka Advisor Maritime Archaeology for the Department

of Archaeology, Sub-Aqua Club and Maritime Heritage Trust

Mr Rukshan Jayewardene Archaeologist; Trainee in Maritime Archaeology

Mr D. Kandamby National Maritime Museum, Galle

Mr Indrajith Kuruppu former member of Galle Harbour Project

Mr Sirinimal Lakdusinghe Director, Department of National Museums

Dr K.D. Paranavitanai Department of National Archives

Drs Robert Parthesius University of Amsterdam

Mr Asoka Perera Post-Graduate Institute of Archaeology

H.E. Mr H.C.R.M. Princen Ambassador of the Netherlands

Mrs L. Princen Mr K.D.S. Silva Post-Graduate Institute of Archaeology

Ms Nerina de Silva Conservator, Consultant Galle Harbour Project

Ms Corioli Souter Western Australian Maritime Museum

Mr Kurarasingha Tennegedara National Museum

Ms Yola Vollebregt Netherlands Embassy

Drs Loderwijk Wagenaar Amsterdam Historical Museum

Mr Chandana Weerasena Central Cultural Fund

Mr K.D. Palita Weerasingha Central Cultural Fund

Mr Indu Weerasoori Southern Development Authority